The University of the Future

When I talk to students, they all seem to agree that something is wrong in Higher Education. “Learning” has degenerated into studying for an end in itself consisting of a rigid structure of acquiring knowledge, remembering it, and reproducing it at a certain point in time (exam), which neither promotes long-term nor independent thinking. In this deadlocked construct of universities, responsible citizens are supposed to be educated, who can exist in a 21st century that is constantly changing. It is obvious, universities have to change. In this blog post, I want to discuss the current, problematic status and first steps to better universities. Let’s build the university of the future. Do not worry, I will be your guide!

Research-Based Higher Education

Many universities in Germany, including mine, see themselves as “Research Universities”. What they mean by that is anchoring the education of students in the (technical) research made by their research labs. What we get from this, is often highly specialized scientists, that are very impactful in research (measured by the number of third-party funds the aquire), but are less experienced in teaching. Combined with the “mass processing” of students, which is certainly also related to the rising overall numbers of students, this often makes for conservative outdated teaching, which is to be criticized: if we want to train students for research, then we must also allow students to research if we want to adhere to competence orientation. To achieve competencies in research learners need to be able to apply knowledge and skills acquired through experience or learning in ever new situations independently, responsibly, and appropriately to the situation. It seems therefore strange how a study program can be research-anchored, although apart from Bachelor’s and Master’s thesis, hardly any independent scientific work is included in the curriculum. For many, these two theses are the only scientific presentations and texts that they produce in their 5+ years of studying. If you want to train the next generation of scientists, you should teach them the skills of a scientist as well as specialist knowledge. Scientific writing, own empirical exploration of ideas, source work, or prototypical implementation are all not components of the current way we are studying.

These deficiencies of science education - even in higher education - are often lamented in politics, by educators and industry leaders alike. Research-based higher education should not mean to only incorporate current research into teaching but also encouraging and requiring teaching to be based on educational research. If educators do not know how we humans learn, we do not have to wonder that higher education does not magically create outstanding individuals. In reality, the students’ lacking learning outcomes seem to have very little impact on course development, and new courses are often designed based on one’s own current research topics instead of according to students’ needs or overall requirements of the study program. This is not to say that there are no good intentions and to belittle the time and effort spent for the education of students, but systematically, a good education is secondary to good research. This sounds suspiciously like a vicious circle: when students are less important than research, the first ideas for scaling the education to more students, are depriving them of their freedom and individuality to reduce the time spent for each. This boils down studying so far, that it lacks almost everything that constitutes studying.

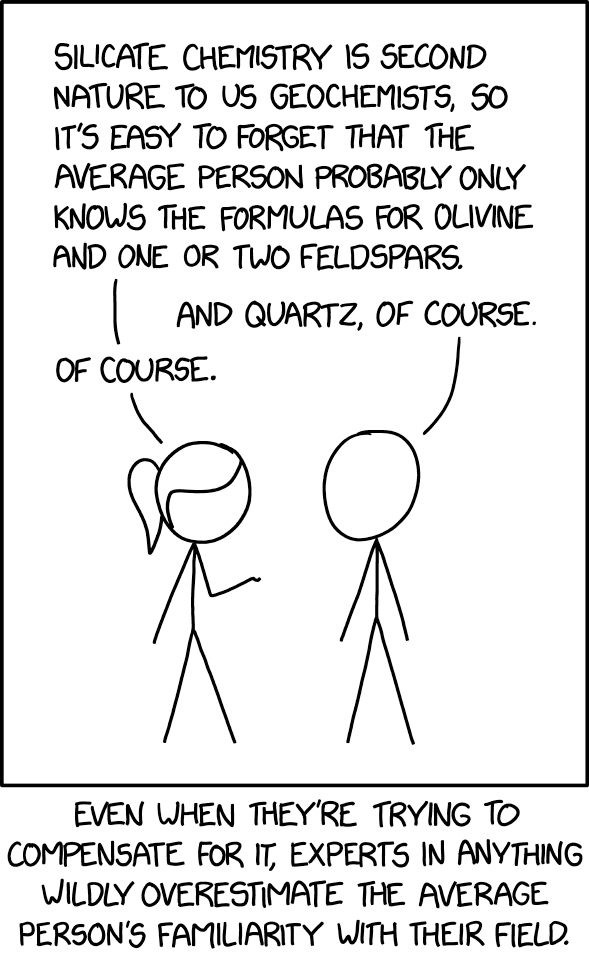

Contribute to this construct, is the curse of knowledge, also called the curse of expertise, which seems to explain this behavior. It states that, when you know something, it is extremely difficult to think about it from the perspective of someone who does not know it. (Wieman, 2007) Applied to education it reveals the bias of educators to think about student learning in terms of what appears best to them, as opposed to what students and research confirm. It is therefore potentially useless or detrimental to ask for an educator’s opinion, instead of empirically verifying assumptions in students learning processes and outcomes. Brain research showed, that when presented with a challenge, novices’ brains are engaged quite differently than experts’ brains. The brain transforms with the creation of new connections and altered activation patterns once mastery is attained. (Hill and Schneider, 2006)

The cartoon explains the curse of expertise by showing a real-world example. The experts (left) “wildly overestimates” the knowledge of a non-expert (right), even if they try to compensate for the differences in knowledge. Students often think about topics in ways not envisioned by educators, and lectures prepared by experts and thought of “logical” and “clear” are interpreted completely differently by the receiver. Crouch et al. (2004) and Roth et al. (1997) even found that the de-facto standard of lecture demonstrations has little effect on learning, and instead “knowing science [should be seen] as competent participation in science-related discourse” (Roth et al., 1997). In practice, students are increasingly denied their autonomy and responsibility. Speaking metaphorically, (higher) education currently seems to consist of watering everything with a “watering can of knowledge”, instead of proceeding in a needs-based, careful and individual manner.

Unwillingness to Change

Thinking of the assessment of students’ learnings one hardly thinks of places of freedom and creativity. In no other field of action educators in higher education allow themselves to be deprived of their freedom of decision, based on labor economic considerations or subject traditions. The reality of assessment at universities is in tension with the postulated goals of competence acquisition. Or in short: Written and most oral exams are unable to determine learning success for the 21st Century Learning Goals, like creative and critical thinking, collaboration, or communication. (Trilling and Fadel, 2009)

At the same time, they know the issues of the practices that arise in the process. Pedagogical and didactical considerations seem to end before exams and innovations in the field of examinations intervene deeply in questions of a teaching/learning culture. They expose completely different self-understandings on behalf of universities. According to a broad consensus, interdisciplinarity, critical-seeking exploration, creative self-responsibility for one’s learning and practical doing are, what constitutes “scientificity,” “academic education” and “university” at its core. Modularized degree programs are advised to provide fixed structures for a growing number of students, where university professors decide directly on module descriptions and examination regulations. Here teaching reforms, that try to bridge the gap between different courses, introduce practical aspects of didactics and pedagogics, or improve student-educator relationships seem to be difficult to impossible to implement, as they rely merely on voluntariness and goodwill of university professors. How is this compatible with the provisions of Article 5(3) of the Basic Law, according to which art, science, research, and teaching are free?(Baier et al., 2018) Hartmer and Detmer (2016) describe this problematic correlation from a legal perspective as follows:

“The freedom of teaching finds its necessary correlate in the freedom of learning of the students. Scientific teaching presupposes that the learners are just as free as the teachers. Only in this way is the process of scientific communication possible, which Article 5 (3) of the Basic Law has in view. A conception that regards the teacher as the bearer of academic freedom but the learner only as a user or customer who makes use of his or her professional freedom fails to recognize that in academic teaching the teacher is always also a learner and the learner is in a certain sense also a teacher.” [translated from German, original by Hartmer and Detmer (2016)]

In a perfect world, all lectures are perfectly coordinated in terms of content, and individual battles have become teamwork. Assessments are made in an authentic way, similar to what students may encounter in their future working environment. The reality is different: good practices of teaching seem to come second behind exceptional research. This is argued with the unclear and not easily quantifiable value of good lectures vs. the measurable impact of research. This leads to a systematic and systemic imbalance, that is impossible to solve bottom up. As peers play the most powerful role in shaping others how to teach, using their power and a top-down approach can lead to sustainable successes. We, as an academic society should therefore encourage and require lighthouse projects, which can trigger a domino effect of educators working on their teaching.(Diamond, 2007)

As shown educators will need to understand more about students’ learning for their instructional practice in the future to create and design courses, laboratories, or seminars successfully, which help students to learn valuable skills. This is essential to make the university an institution for now and for future times, where

- “the permanent change of work and life requirements

- the individualization of biographies with multiple discontinuities

- the pluralization of social milieus and lifestyles

- the shortening half-life of (factual) knowledge (with significantly slower obsolescence of basic knowledge and methods)

- the dissolution of traditional structures.” [translated from German, original by Webler (2005)]

are sufficiently considered.

This necessitates a shift in the general framework of study programs, enabling students to study independently. In the first semesters, students need to acquire solid work practices, scientific reading, and writing, but also focused individual learning strategies and methods of arranging autonomous group work - not in theoretical classes, but based on subject content. Instead, school-like degree programs are marked by a negative image of students, on which students are given an advance of mistrust and can only be kept on a good path by pressure and regulation, reflected in a high number of exams and other proofs of achievements. (Webler, 2005)

In the end, each lecture and each associated assessment has to pass the test of whether or not it is relevant to the student’s professional future. This is by no means an easy task; it requires a willingness to innovate on the part of the teachers, who have to meet the actual - not the assumed - needs of the students.

An idea

So far so bad, so how could we change that? We will work on this from my example: students learning informatics and information technology. Currently, this subject (in the Master) is very exam focussed: in the examination period after each semester, you are assessed on knowledge. This usually means spending about two weeks of intense studying with the main objective of acquiring disposable knowledge that is not applicable to most real-world problems. Additionally, the degree consists of a practical seminar or lab, which is also usually concluded with a written or oral examination, a master thesis, and some sort of soft skill seminars like a language course.

I want to (re-)imagine studying. The idea is not to think so much about what is legally impossible, who is supposed to pay for it or take care of it, etc, but to describe a concept.

First of all, no more written exams! Especially in graduate programs, written exams almost always fail to meaningfully assess skills. Instead, they focus on needless memorization, essentially only “to chew up and vomit out” learned times. Not to say memorization is not an important skill, but as the main objective, it fails the test of skills acquired. So how are we gonna check skills then? Let me tell you the magic idea:

A Portfolio! Every student when starting their master’s degree creates an online portfolio, based on which the performances are evaluated. We kill two/three birds with one stone, by allowing students to train scientific writing, narrating their learning journey, which can be a skill in itself, and building a portfolio that showcases their work to future employers or their peers. Students reflect on their work by continuously revising their synthesis or analysis until both teacher and student are satisfied. With a changed error culture in which it is no longer true that an error equals solely a bad grade, but an error is seen as an opportunity for change, self-improvement, and learning. Learning does not end with the exam but goes beyond it, as portfolios integrate the assessment process as part of learning.

Lectures can be easily replaced by seminars, where after introduction, students work in groups (maybe in a eduscrum fashion) or alone on a research project, the results of which are discussed in the group again. Even if the assessment of these results is a high burden on educators, it can be done using Peer Assessment or Feedback. Good seminars with the guidance of educators can even benefit both sides: students participating and helping with actual research plus a teaching team, who get new inputs or even outsource small parts of their work.

An example

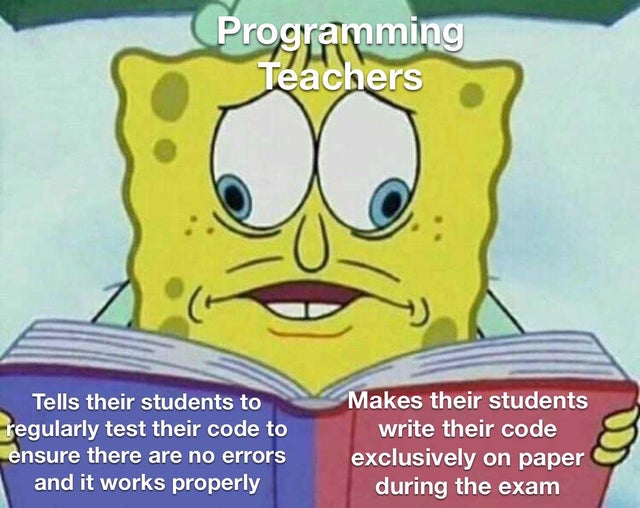

A meme take on programming education, one can wonder how paper exams for programming and the reality of test-driven development, debugging, and the internet as the main resource are compatible.

A meme take on programming education, one can wonder how paper exams for programming and the reality of test-driven development, debugging, and the internet as the main resource are compatible.

So let’s close with an example in my study subject - Information Technology with an actual practical concept. So the portfolio for any programmer is a GitHub profile. So how revolutionary would it be if, because of my university degree, I already have a filled GitHub Profile? Not only will I have worked with the tools that are relevant to my future employment, like Git, but I am also able to showcase all my academic achievements and their contents, instead of having a paper sheet with grades on it, whose learning outcomes are completely unclear for external parties. Even if my future employer is not interested in the details, I can come back any time and see/use the things I have learned.

But it is not only viable for programming code:

- Did a literature review? Put your thoughts in Blog form and host it for free with Github Pages

- Some scientific writing? Add the LaTex files to your profile

- Learned about CI/CD? You can try it out on GitHub directly, e.g. build a docker container from your files.

In the end, the whole lifecycle from the first term to your master thesis can be developed openly and freely for everyone to see. No more closed doors of what I learned and trying to explain what I did in my Master’s. And even for educators, this offers new opportunities, as tools surrounding Git can improve their workflow massively and lead to immense time savings.

Let’s do this

We as students and the other stakeholders should work together to make this university of the future a reality. We need to stop denying students their autonomy and instead put them at the center of university learning. This means recognizing their real needs, addressing them politically, in small and large ways, and entering into the resulting processes of change with confidence and courage. This blog post argues that students in higher education are not learning driving by

- a systematic unwillingness to change

- a focus on the assessment that seems unavoidable from a teacher’s point of view

- a bias toward excellent research instead of excellent education, that leads to the lack of competence orientation

- a subconscious expert bias of educators in higher education.

These issues can be addressed by

- creating study subjects as a team bottom-up instead of the top-down ivory tower thinking of many

- new learning formats, that are interdisciplinary, focus on producing instead of consuming and teamwork, with regular feedback and guidance instead of a one-time final assessment

- Student representation and participation from day one to make students the center of the education and shift the spotlights from teaching to learning

I would love to hear what you think. Feel free to send me a message at simon@simonklug.de. Many thanks to Sebastion for your Input and Feedback.

Bibliography

André Baier, Hans-Joachim Bargstädt, Sabine Doff, Frédéric Falkenhagen, Inga Gryl, Sabina Fleitmann, Theresa Jansen, Franz-Josef Schmitt, Edith Kröber, Oliver Reis, Stephan Jolie, Bastian Küppers, Christian Seifert, Silke Masson, Jürgen Schlegel, Birgit Szczyrba, Timo van Treeck, and Marco Winzker. Wie frei soll und kann die lehre sein? - 7. lehr-/lernkonferenz. 2018. ↩

Catherine Crouch, Adam P Fagen, J Paul Callan, and Eric Mazur. Classroom demonstrations: learning tools or entertainment? American journal of physics, 72(6):835–838, 2004. ↩

John B Diamond. Where the rubber meets the road: rethinking the connection between high-stakes testing policy and classroom instruction. Sociology of Education, 80(4):285–313, 2007. ↩

Michael Hartmer and Hubert Detmer, editors. Hochschulrecht: Ein Handbuch für die Praxis. C.F. Müller, 12 2016. ↩ 1 2

Nicole M Hill and Walter Schneider. Brain changes in the development of expertise: neuroanatomical and neurophysiological evidence about skill-based adaptations. 2006. ↩

Wolff-Michael Roth, Campbell J McRobbie, Keith B Lucas, and Sylvie Boutonné. Why many students fail to learn from demonstrations? a social practice perspective on learning in physics. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 34(5):509–533, 1997. ↩ 1 2

Bernie Trilling and Charles Fadel. 21st century skills: Learning for life in our times. John Wiley & Sons, 2009. ↩

Wolff-Dietrich Webler. «Gebt den Studierenden ihr Studium zurück!» Über Selbststudium, optimierende Lernstrategien und autonomes Lernen (in Gruppen). Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerbildung, 23(1):22–34, 2005. ↩ 1 2

Carl Wieman. The "curse of knowledge" or why intuition about teaching often fails. American Physical Society News, 2007. ↩

#change #university